A mother's oral health before and during pregnancy influences the health of both mother and child. You should take care of your oral health throughout your life, but it is especially important when trying to conceive and as part of good prenatal care. Equally important, mothers can pass good oral health and good oral hygiene to their children, starting their mouths off right. Good prenatal oral health can even help prevent cavities in your children. Learn what you can do to ensure good oral health for you and your child before, throughout and after your pregnancy here.

Oral microbiome and oral disease

Our mouths are home to a community of hundreds of species of bacteria and other microbes (fungi, viruses) known as our oral microbiome. Some species help keep us healthy, aiding in breaking down food, producing vitamins, and fighting off infection.

Other species are pathogenic (disease-causing) and release chemicals that can damage our mouths. Some produce acid that erodes tooth enamel and causes cavities, and if left untreated, can cause tooth loss. Others release toxins that trigger chronic inflammation. Chronic inflammation is what leads to gum diseases like gingivitis or periodontitis [1].

When we’re healthy, our oral microbiomes are in balance. But when this ecosystem becomes unbalanced (oral dysbiosis), pathogenic species grow in number and lead to cavities, inflammation and oral disease.

Oral health and pregnancy

How pregnancy affects mothers’ oral health

Mothers’ bodies undergo many natural changes during their pregnancies. We’ll explore how some of these changes can impact mothers’ oral health below.

Hormones

Mothers’ hormone production changes during pregnancy, mostly with increased production of estrogen and progesterone. These hormones play essential roles in the babies’ development. Estrogen aids in the formation of new blood vessels, nutrient transfer, and milk duct formation. Progesterone, among other effects (morning sickness), loosens joints and ligaments throughout the body, and is essential in increasing the size of the uterus and other tissues to accommodate a full-term baby and childbirth [2].

These hormones also increase blood flow to the gums, making them more sensitive to the presence of plaque and pathogenic bacteria [3].

Diet

Many mothers will experience a change in their diets during pregnancy. The most commonly cited reasons for changing diet include the need for more calories to fuel fetal growth, avoiding risks to fetal health (like raw fish, eggs, etc.), changes in taste perception, and nausea (aka morning sickness). Specific dietary changes, such as an increase in sweet food consumption or more frequent snacking, may increase a mother’s risk of cavities due to an increase in dietary sugar and carbohydrates [4].

Morning sickness

Morning sickness is nausea and vomiting that occurs during pregnancy, although it can occur at any time of day. Many women will experience morning sickness during their pregnancy, especially during their first trimester. Vomit contains stomach acids that can erode the enamel in your teeth and increase the risk of tooth decay [5]. Rinsing your mouth after vomiting is a good idea, whether you are pregnant or not.

Gag reflex

During pregnancy, some mothers may develop more sensitive gag reflexes, making brushing their teeth uncomfortable and more difficult, leading to brushing less often. Sensitivity to the taste of toothpaste may also be a factor. This reduced brushing increases a mother’s risk of developing cavities or gum disease due to a lack of proper hygiene [6].

Oral microbiome

Scientists have observed significant changes in mothers’ oral microbiomes during pregnancy due to hormonal changes. Several studies have observed an increase in gum disease-causing bacteria, including P. gingivalis and T. forsythia, which may increase a mother’s risk of developing gum disease [7]. Moreover, oral microbiome data have shown potential to predict adverse pregnancy outcomes, although further research is needed to confirm their predictive potential.

Pregnancy and Dental Cavities (Caries)

Mothers and Dental Cavities

Mothers face an increased risk of developing dental cavities (caries) during pregnancy because of dietary changes, morning sickness, and reduced oral hygiene practices due to nausea and the gag reflex. Many of these changes have been shown to subside post-pregnancy.

Children and Dental Cavities

Oral bacteria, including those that cause cavities, can be passed from person to person in saliva. This is especially common between parents and their children, through kissing, feeding, touching, etc. Children of mothers who have high levels of untreated cavities or tooth loss are more than three times more likely to have childhood cavities [8].

Thankfully, studies have found that mothers receiving prenatal oral health care can reduce their child’s risk of early childhood cavities [9]. Reinforcing that good prenatal oral health is essential to a child’s oral health.

Pregnancy and Gum Disease

Gingivitis

Gingivitis is a common, mild form of gum disease. It is the result of the gums becoming inflamed in response to an infection by pathogenic bacteria. Almost half (46%) of US adults over age 30 have some form of gum disease [10].

Gingivitis is common during pregnancy, with 60-75% of mothers experiencing some form of gum inflammation. This is primarily due to the increased blood flow, permeability and sensitivity of their gums caused by elevated estrogen and progesterone levels. Pregnancy gingivitis usually starts at the second month of gestation and reaches the highest level at the eighth month [11].

When good oral hygiene practices are implemented, pregnancy gingivitis usually resolves within a few months of birth. Pregnancy gingivitis is not believed to be a risk factor for adverse pregnancy outcomes [12].

Periodontitis

Periodontitis is a more severe form of gum disease that can lead to tooth loss and jawbone damage. Unlike pregnancy gingivitis, periodontitis is typically unrelated to pregnancy status or hormones. Rather, it is caused by a chronic, advanced infection of the gums by pathogenic bacteria.

Periodontitis has been associated with an increased risk of heart disease, dementia/Alzheimer’s disease, autoimmune disease, and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Therefore, women intending to become pregnant (even those not actively using birth control methods to prevent pregnancy) should be especially diligent about oral hygiene and dental care to prevent or treat periodontitis.

Loose teeth

Mothers may notice their teeth feeling loose during the later stages of their pregnancies. This is caused by increased levels of estrogen and progesterone and generally resolves postpartum [13].

Pregnancy tumors

Some mothers will develop soft, red, swollen growths on their gums called pyogenic granulomas. These are often referred to as “pregnancy tumors,” but they are not cancerous and are believed to be caused by an increase in estrogen and excess plaque. They occur in 5% of mothers, most frequently in the 2nd and 3rd trimesters. They will usually resolve themselves postpartum but can be removed if necessary [14].

Gum disease and adverse pregnancy outcomes

Adverse pregnancy outcomes (APOs) occur in a significant number of pregnancies, often without a known cause. APOs include preterm birth, low birth weight, preeclampsia (a potentially dangerous rise in blood pressure), and spontaneous fetal death.

APOs can have lifelong consequences on children. 52% of infants born early at 24-28 weeks have neurodevelopmental impairment compared to 5% of those born near term at 32-36 weeks. Adults born with very low birth weight had lower bone mineral density than their term-birth, normal-weight, same-age peers [12].

How gum disease may affect pregnancy

Currently, there are two hypotheses for how gum disease may influence adverse pregnancy outcomes: direct pathogenic influence and indirect inflammatory influence.

Direct pathogenic influence

When the gums become inflamed, they are easier to cut or wound, which allows harmful bacteria to enter the bloodstream (bacteremia). Once in the blood, pathogenic bacteria may settle and colonize in distant places around the body, triggering inflammation and releasing toxins that can lead to disease.

The direct pathogenic influence hypothesis in pregnancy proposes that pathogenic bacteria that enter the bloodstream accumulate and colonize on the placenta, leading to placental or fetal damage. Studies have supported this hypothesis, finding that the placental microbiome is more similar to a mothers’ oral microbiomes than their gut microbiomes [15].

This hypothesis has been tested in animal models. One study injected a known gum-disease causing bacteria, F. nucleatum, into the tail of a pregnant mouse to mimic bacteremia. An examination found bacterial colonies in the placenta, followed by a spread to the fetal membrane. This led to preterm and term fetal death, occurring 2-3 days following bacterial injection [16].

Indirect pathogenic influence

When our bodies detect infection by foreign invaders, certain immune cells release molecules, called proinflammatory cytokines, that alert the rest of our immune systems to fight off the infection. This is an integral part of our immune response that helps keep us healthy when we suffer cuts that allow bacteria into our bodies, or when we catch a cold or other respiratory infections.

Some diseases, like gum disease, trigger chronic inflammation, which means our bodies will continually produce these cytokines in large amounts. Over time, these cytokines build up and spread through the body via the bloodstream, making our bodies think the signals are coming from places other than just our mouths.

The indirect pathogenic influence hypothesis proposes that these cytokines may send incorrect signals near the placental-fetal junction, leading to adverse pregnancy outcomes [16].

Elevated levels of cytokines have been observed in mothers with adverse pregnancy outcomes, but studies remain inconclusive. There have been studies in several animal models, including rats and baboons, attempting to mimic this hypothesis, but results have been contradictory, with different outcomes in different subsets of animals [16].

Types of adverse pregnancy outcomes

Low birth weight

Low and very low birth weight is defined as the baby weighing <2,500g (5lbs, 8oz) and <1,500g (~3lbs, 4oz), respectively. Low birth weight affects 8.3% of births, and very low birth weight affects 1.3%.

A research group reviewed 15 available studies on mothers with periodontitis and their pregnancy outcomes. They found that mothers with periodontitis had an increased risk of delivering babies with low birth weights [12].

One known risk factor for low birth weight is an overgrowth of anaerobic bacteria in the vagina (bacterial vaginosis). Anaerobic, meaning “without oxygen,” species grow and survive where there is no oxygen. Since healthy vaginas are colonized by a small number of aerobic bacterial species (unlike the gut, where more diversity is associated with better health), the presence of such bacteria is a sign of dysbiosis, even infection.

Similarly, gum disease is caused by an overgrowth of anaerobic species living below the gum lines in our mouths (which is why it’s crucial to floss!). Two of the most common gum disease-causing species, P. gingivalis, and F. nucleatum, have been found in the vaginal and placental microbiome of mothers with low birth weight.

This brings up a possibility that the anaerobic bacteria from the mouth may build up in the placenta and cause inflammation and damage, similar to how they do in bacterial vaginosis [12].

Preterm birth

Preterm birth is defined as a delivery taking place before 37 completed weeks of pregnancy. Preterm births affect 1 in 10 infants born in the US. Babies born before 32 weeks of pregnancy have higher rates of death and disability [17]. They are also likely to be low birth weight.

The same review of 15 studies found mothers with periodontitis faced nearly three times the risk of preterm birth than mothers with full-term births [12].

Inflammatory signals (like the cytokines we discussed) are naturally elevated during labor. The inflammatory signals from gum disease or infection of the placenta might mistakenly induce preterm labor, leading to preterm births.

Several oral pathogens have been detected in the placenta of mothers who had preterm births. One of them, P. micra, was detected in the placentas of preterm births - and not in mothers with full-term pregnancies without periodontitis.

Another common oral pathogen (F. nucleatum) is one of the most prevalent bacteria found in intrauterine infections and is not present in a normal vaginal microbiome. It was detected in 94% of placentas from preterm births and only 36% of placentas from mothers with full-term births and no periodontitis.

Interestingly, a bacteria found in healthy mouths, A. israelii, was detected more frequently in mothers with full-term, normal-weight births [12].

Preeclampsia

Preeclampsia is a condition that affects 2-5% of pregnancies. Symptoms of preeclampsia are rapid high blood pressure, swelling of hands and feet, and protein in the urine after the 20th week of pregnancy [16]. Preeclampsia has been associated with chronic inflammation.

Again it is suspected that oral pathogenic bacteria may play a direct or indirect role in triggering this inflammation. Some species, like F. nucleatum, were detected in placental samples from mothers with preeclampsia and were not detected in healthy mothers. Others, like P. gingivalis, were found at significantly higher levels than in healthy mothers [12].

Spontaneous fetal death

Preterm fetal death can occur <20 weeks into pregnancy (miscarriage) or between 20 to 36 weeks (stillbirth). It’s estimated that as many as 26% of pregnancies end in miscarriage, with 80% occurring in the first trimester. Stillbirth affects 1 in 160 pregnancies (0.6%).

One case study found an identical copy of the gum disease pathogen F. nucleatum in the placenta of a stillborn infant and the mouth of its mother, who experienced excessive gingival bleeding during pregnancy [12].

This has been explored in animal models as well, which have demonstrated the ability of oral pathogens to induce fetal death. One study administered toxins from the oral pathogen P. gingivalis to pregnant rats. They observed it induced fetal resorption (disintegration of the fetus).

Another study injected antibodies made against P. gingivalis into pregnant mice, and observed fetal loss [18]. This would be an indirect effect mediated through the mother’s immune system.

Preventing Oral Disease before and during Pregnancy

Thankfully, there are steps mothers can take to reduce their risk of oral disease during pregnancy and their child’s risk of oral disease. These include:

As with all emerging research, keep in mind that these studies and their results are not deterministic. Researchers are working to understand the role of oral health and the oral microbiome on our overall health. There is currently no evidence that proves beyond a doubt that oral pathogens cause adverse pregnancy outcomes. Do not interpret the information in this article or in the papers we cite as medical or dental advice.

On the other hand, it is a well-established fact that good oral health is (at the very least) an important component of good overall health. We encourage all of you to take steps toward improving your oral health and minimizing the risk for oral disease. This is especially important because your oral health affects your children’s oral health.

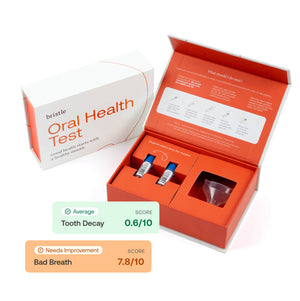

At Bristle, we believe that addressing and improving your oral health is one of the most essential and actionable steps in improving the health of our whole bodies. Through our tests and insights, we can provide anyone with better tools to improve their oral health. Lots of small improvements—many of them easy to do—can create a massive positive impact on our overall health—so we think your mouth is a pretty great place to start.

Limitations of studies

Shared risk factors

APOs and periodontitis have many risk factors in common, so it’s important to consider that these risk factors may all play a role.. Notably, increased maternal age is associated with both increased prevalence of periodontitis and adverse pregnancy outcomes [12].

Differing definitions of periodontitis

The definition of periodontitis varies from study to study, largely because the diagnosis is based on researcher’s observations. This means that one study may classify a patient as having periodontitis, when another study may classify that same patient as not having periodontitis [12].